Bad Credit Shouldn't Block Employment: How to Make State Bans on Employment Credit Checks More Effective

Over the last ten years, a growing number of cities and states passed laws limiting the use of credit checks in hiring, promotion, and firing. Lawmakers are motivated by a number of well-founded concerns: although credit history is not relevant to employment, employment credit checks create barriers to opportunity and upward mobility, can exacerbate racial discrimination, and can lead to invasions of privacy. This report examines the effectiveness of the employment credit check laws enacted so far and finds that unjustified exemptions included in the laws, a failure to pursue enforcement, and a lack of public outreach have prevented these important employment protections from being as effective as they could be.

- Eleven states have passed laws limiting the use of employment credit checks. State laws to limit employer credit checks were enacted in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington. Cities, including New York City and Chicago, have restricted credit checks as well.

- Credit check laws are effective at increasing employment among job applicants with poor credit. A new study from researchers at Harvard and the Federal Reserve Bank finds that state laws banning credit checks successfully increase overall employment in low-credit census tracts by between 2.3 and 3.3 percent.

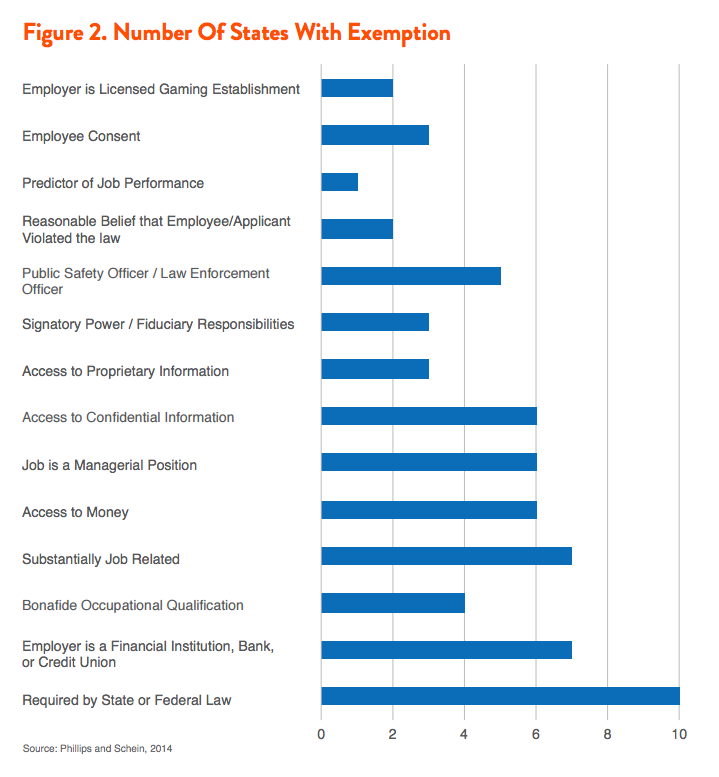

- Despite important goals of reducing barriers to employment and eliminating a source of discrimination, existing state laws on credit checks are undermined by the significant exemptions they contain. Although exemptions are not justified by peer-reviewed research, many state credit check laws include broad exemptions for employees handling cash or goods, for employees with access to financial information, for management positions, and for law enforcement positions. Some legislators also express concern that the number of exemptions that were ultimately included in the laws make them more difficult to enforce.

- Demos research found no successful legal actions or enforcement taken under the laws, even those that have existed for a number of years. While the existence of the laws themselves may deter the use of employment credit checks, it is unlikely that every employer is in full compliance with the laws. Instead, the lack of any enforcement action against employers violating the laws suggests that credit check restrictions are not as effective as they could be.

- A lack of public awareness on the right to be employed without a credit check may undercut effectiveness. A key reason that states have not taken enforcement action is because they receive very few complaints about violations of the law. Demos finds that public education and outreach efforts about the credit check laws have been minimal in many states, suggesting that few people are aware of their rights.

- New York City’s new law restricting the use of employment credit checks is an improvement on past laws. In 2015, New York City passed the nation’s strongest law restricting employment credit checks. While New York’s law still contains a number of unjustified exemptions, these exclusions are narrower than in many other credit check laws, and New York’s public outreach effort is exemplary.

To learn more about the problems with employment credit checks that motivated many states laws, see Demos’ report, Discredited: How Employment Credit Checks Keep Qualified Workers out of a Job.

Introduction

Over the last ten years, a growing number of cities and states passed laws limiting the use of personal credit history in employment, also known as employment credit checks. Lawmakers are motivated by a number of well-founded concerns: although credit history is not relevant to employment, employment credit checks create barriers to opportunity and upward mobility, can exacerbate racial discrimination, and can lead to invasions of privacy. States laws to limit employer credit checks were enacted in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington. Delaware has also restricted the use of credit checks in hiring for public employment. Cities, including New York City and Chicago, have restricted credit checks as well.1 In 2014 there were 39 state bills introduced or pending aimed at limiting the use of credit checks in employment decisions, as well as federal legislation proposed in the House and Senate.2 This report examines the impact of the credit check laws enacted so far, considers barriers to their effectiveness and discusses strategies to increase protections for workers.

In researching this report, Demos conducted a search of legal databases Westlaw and Lexis Nexis for cases brought under each statute, queried enforcement officials in each state about complaints and enforcement actions taken under the law, and contacted legislators for their impressions on the effectiveness of the legislation. We begin by looking more closely at the practice of employment credit checks and exploring the motivation for restrictions.

What Are Employment Credit Checks?

Credit checks are widely used by employers making hiring decisions.3 The federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) also permits employers to request credit reports on existing employees for decisions on promoting or firing workers.4 While employers generally cannot access three-digit credit scores, they can obtain credit reports that include information on mortgage debt; data on student loans; amounts of car payments; details on credit card accounts including balances, credit limits, and monthly payments; bankruptcy records; bills, including medical debts, that are in collection; and tax liens. Under the statute, employers must first obtain written permission from the individual whose credit report they seek to review. Employers are also required to notify individuals before they take “adverse action” (in this case, failing to hire, promote or retain an employee) based in whole or in part on any information in the credit report. The employer is required to offer a copy of the credit report and a written summary of the consumer’s rights along with this notification. After providing job applicants with a short period of time (typically three to five business days) to identify and begin disputing any errors in their credit report, employers may then take action based on the report and must once again notify the job applicant.

Credit reports were developed to help lenders assess the risks associated with making a loan. Over the last few years, they have been aggressively marketed to employers as a means to gauge an applicant’s moral character, reliability or likelihood to commit theft or fraud. While the practice of checking credit may appear benign, a growing body of research suggests that credit checks do not accurately measure employment-related characteristics and may instead bar many qualified workers from employment. A 2013 Demos report found that 1 in 10 unemployed workers in a low or middle-income household with credit card debt were denied a job because of a credit check.5

Why Restrict Employment Credit Checks?

Credit checks bar qualified workers from jobs because poor credit is associated with unemployment, medical debt and lack of health coverage, which tell very little about personal job performance, but rather reveal systemic injustice, individual bad luck, and the impact of a weak economy.6 The financial crisis and the Great Recession caused millions of Americans to be laid off from their jobs, see their home values plummet to less than their mortgage debt, and find their savings and retirement accounts decimated – all of which can affect credit history. Even seven years after the initial stock market crash, wages for all but the top 95th income percentile have not recovered.7 Though job markets have recovered to some extent, the recovery has been slow and many Americans have been left behind.8 These are largely factors that are outside an individual’s control and have no reflection on someone’s “moral character” or their ability to adequately perform their job. Rather, credit checks are unfair and discriminate against the long-term unemployed and other disadvantaged groups, creating a barrier to upward mobility.

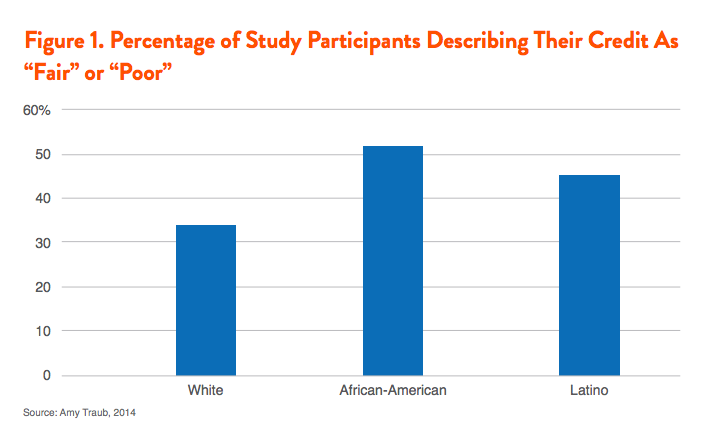

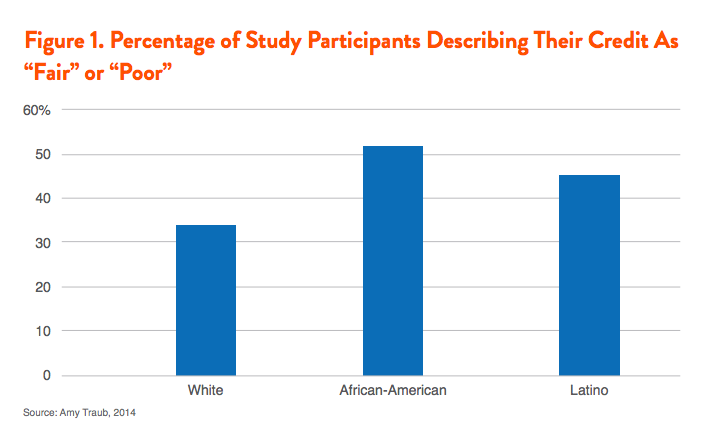

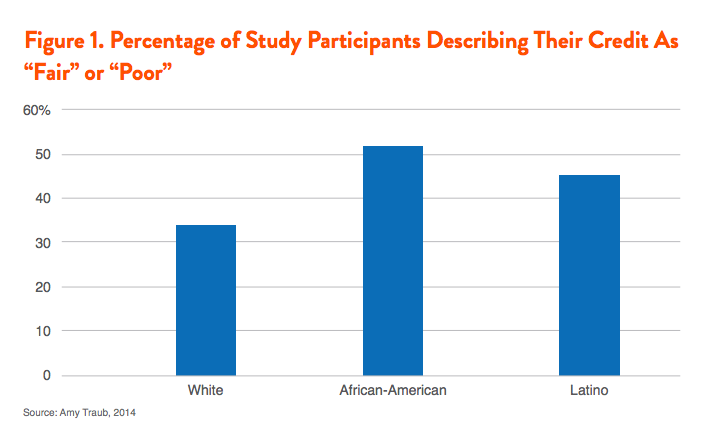

Because of the legacy of predatory lending and racial discrimination, people of color tend to have lower credit ratings than whites, and so may be disproportionately likely to be denied a job because of a credit check.9 A persistent legacy of discriminatory lending, hiring, and housing policies has left people of color with worse credit, on average, than white households.10 In recent years, historic disparities have been compounded by predatory lending schemes that targeted low-income communities and communities of color, putting them at greater risk of foreclosure and default on loans, further damaging their credit.11 By evaluating prospective employees based on credit, employment credit checks can further extend this injustice.

Worryingly, credit reports are often riddled with errors. A Demos study of low- and middle-income households carrying credit card debt finds that 1 in 8 respondents who have poor credit cite “errors in my credit report” for their credit problems.12 A Federal Trade Commission (FTC) study finds that five percent of consumers, amounting to 45 million Americans, had errors on at least one of their three major credit reports.13 A follow-up study finds that majorities of these consumers still have outstanding errors on their credit report.14 A 2011 industry-funded study by the Policy and Economic Research Council (PERC), found that 1 in 5 people who reviewed their credit report found incorrect information and 12.1 percent of those errors could have a material impact on their score.15 As a result of employment credit checks, individuals can be disqualified from job because of a credit report that is not even factual.16 As the New York Times editorial board noted, “the interest around this issue shows that more law makers are starting to realize how this unfair practice damages the lives and job prospects of millions of people.”17

The invasion of privacy is another concern when personal credit information is used in employment. Not only do credit reports reveal a great deal about an individual’s personal financial history, they also provide a window into even more deeply private matters such as medical history, divorce, and cases of domestic abuse. For example, surveys find that when a credit check is conducted, employers often ask individuals with flawed credit to explain why they are behind on their bills.18 Given that past due medical bills make up the majority of accounts reported by collection agencies, many prospective employees will feel obliged to discuss their otherwise confidential medical histories as a pre-requisite for obtaining employment. Since divorce and domestic abuse are other leading causes of credit struggles, a discussion of these often painful and deeply private personal issues can also become compulsory if an job-seeker is asked to “explain” their poor credit to a prospective employer.

Strengths and Weaknesses of State Laws on Employment Credit Checks

Concerns about employment credit checks led to numerous state laws to limit them: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington have all passed legislation. In 2014, Delaware passed a more limited law preventing public employers from using credit checks for employment decisions.19 Chicago has also passed a law prohibiting credit checks from being used in employment decisions.20 More recently, New York City banned credit checks, and made an effort to limit exemptions (see page 16).21 There is evidence that there is broader interest, however, since thirty-nine bills in 19 states were introduced in 2014.22 In addition, legislation has been presented at the federal level, including a bill by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (in the Senate) and Rep. Steven Cohen (in the House).23 This report explores the effectiveness of the credit check laws, and finds that lack of clear enforcement mechanism, exemptions and a robust public outreach effort have all undermined the effectiveness of credit check laws.

Credit Check Laws Lift Employment in Areas with Poor Credit

New research by Robert Clifford at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and Daniel Shoag at Harvard University’s Kennedy School suggests that credit check laws are effective at increasing employment among job applicants with poor credit.24 Drawing on credit bureau and employment data, the authors find that state laws banning credit checks increase overall employment in low-credit census tracts by between 2.3 and 3.3 percent. Despite exemptions that enable employers to continue conducting credit checks for many job categories, the authors find that credit check laws also led to a significant 7 to 11 percent reduction in employer use of credit checks.25 The largest impact on jobs was found in the public sector, followed by employment in transportation and warehousing, information, and in-home services.

The authors find that as the use of credit information in hiring declined, employers elevated other employment criteria, increasingly requiring college degrees or additional work experience. Given that these factors contain more relevant information about job performance than credit checks, this is a step forward.26 However, inflating job requirements beyond what a given position genuinely demands may present its own problems, erecting new and unnecessary barriers to employment. Inflating employment criteria may help to explain a troubling finding of the study: African-American workers experience slightly worse employment outcomes relative to white workers in states that have restricted employment credit checks. The authors of the study have acknowledged a number of uncontrolled variables (such as the over-representation of African Americans in public employment in states that have enacted employment credit check restrictions) may have skewed this result.27 Nevertheless, it raises an important warning: credit check laws by themselves cannot eliminate employment discrimination, and policymakers must remain alert for the resurgence of discriminatory practices.

Credit Check Laws Include Unjustified Exemptions

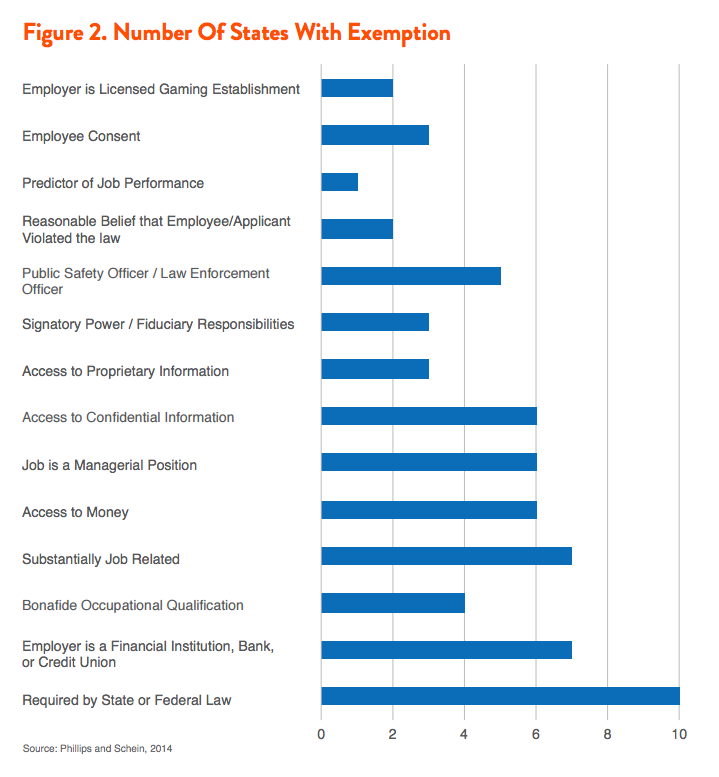

While state laws were ostensibly enacted to prevent employment credit checks from becoming an employment barriers for qualified workers, we find that these laws have been undermined by the numerous broad exemptions they contain. Currently, all state credit check laws include exemptions – job categories where credit checks continue to be permitted even as the law bans credit checks for other positions. Because these exemptions are often vague and cover large categories of workers, they have reduced the effectiveness of state laws. The most common exemptions are provisions that allow for a credit check if it is “substantially job related” or the employer is a financial institution. Other laws contain exemptions permitting credit checks for management positions, law enforcement jobs, or employees with access to cash or goods.

In an analysis of exemptions in state credit check laws, James Phillips and David Schein argue that states restricting employment credit checks “have virtually gutted those restrictions by exception.”28 Legislators themselves have expressed concern about the significant exemptions that were ultimately included in the laws. In Vermont, Helen Head, Chair of the Committee on General, Housing & Military Affairs tells Demos that, “We are concerned that the large number of exceptions may make it more difficult to limit the practice of employer credit checks. In hindsight, I wish we had worked even harder than we did to limit the broad exclusions that were passed in the Vermont bill.” Vermont Representative Kesha Ram echoed the sentiment, noting that, “we included a number of exemptions in terms of types of employment and that these may limit the effectiveness of the law.” These exemptions both make it more difficult for employees to know whether they can seek damages, and also more difficult for courts to rule in their favor. Further, exemptions can hamper enforcement, by making it more risky for the government agency tasked with enforcement to determine whether there has been a violation.

While these exceptions appear to have deeply hampered the effectiveness of these laws, their merit is dubious. The section below examines these exemptions and shows why most are unjustified and unnecessary.

Credit checks are not justified for employees handling cash or goods

As Phillips and Schein note, “nearly every state has articulated specific job-related requirements that make clear when these exceptions are applicable and under what circumstances they will provide an employer with legally sufficient grounds to make a credit history check a requirement or condition of the employment.” They further note that, “exceptions to the ten state statutes have virtually swallowed those states’ legal prohibitions [indicating] that under state law, an employer is virtually free to utilize credit reports to make employment decisions.”35

Credit Check Laws Go Largely Unenforced

States have a range of enforcement mechanisms for laws restricting employment credit checks. Some states give enforcement authority to the Department of Labor/Labor Commission (Connecticut, Colorado, Maryland, Nevada, Oregon) others to the Attorney General (Washington), one to the Department of Fair Employment and Housing (California), and one to the Civil Rights Commissioner (Hawaii) and Vermont splits enforcement between two agencies. In addition, Hawaii, Illinois, Nevada, Oregon and Vermont allow employees or jobseekers harmed by violations of the law to bring a private lawsuit against the violator. One significant shortcoming of many state enforcement efforts is that states are making little investment in investigating employment and hiring practices to detect violations of the law. Instead, the burden is placed on employees and job-seekers who had their credit checked in violation of the law to file a complaint before any action can be taken. Because potential employees may not know a violation has occurred, or even know that they are protected from employment credit checks, placing the burden on employees makes it far more likely that these laws will go unenforced.

Demos contacted state officials for insight on how these laws are being enforced.

- In Connecticut, Nancy Steffens, the Communications Director of the Department of Labor tells Demos that there have been no complaints found to be meritorious. In the four year period since the law went into place, only two complaints had been filed with the Wage and Workplace standards division.

- In Maryland, Geoff Garner, the Program Administrator of the Worker Classification Protection Unit, tells Demos that “only two actual complaints since the law went into effect. Both complaints were investigated and resolved informally (without citations or fines).”

- Charlie Burr, the Communications Director for the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries provided data on the eight cases that have been filed since the law was passed in 2010, which he notes is, “important worker protection, but it’s still relatively new.” The data he sent include eight cases over a four year period, with two under investigation at the time of inquiry. Three of the cases were closed because no substantial evidence of a violation was found. Another was settled privately, another withdrawn from court and the final led to a negotiated conciliation.

- In Vermont, one official in the Civil Rights Department of the Attorney General tells Demos that credit checks are “not really on our radar” at the office mainly because the department doesn’t have authority to audit and thus must wait for complaints. However, since only one complaint was ever filed, and the adverse consequence stemmed from a criminal background check, not an employment credit check, no enforcement resulted. Vermont tasked the Vermont Human Rights Commission with enforcing the credit check law for state employees. However, an official there tells Demos, “The HRC has not gotten any complaints about credit reporting since the law was enacted.”

- In Colorado, the Department of Labor is tasked with enforcing the employment credit check law. Elizabeth Funk, Labor Standards Administrator, tells Demos, “Since 2013, the Division has received several complaint forms. I would say approximately 10 - 20 complaints, and over 100 inquiries in the form of email and phone calls.” She reports that, “Of the approximately 10-20 complaints, I would say half have led to an investigation conducted by our Division. The law gives the Division discretion to assess a penalty if an employer is found in violation of the law. “ As of yet, however, she notes that, “We are still in middle of the investigations so no penalties have been levied at this time.”

- In Washington, enforcement falls under the state’s Fair Credit Reporting Act, which is enforced by the Attorney General. The Attorney General’s Office declined to make information about the number of complaints received or actions taken available.

- In California, the department tasked with enforcement, the Department of Fair Employment and Housing, tells Demos that they don’t have a central database of complaints, and therefore could not provide an estimate. Herbert Yarbrough, the Administrator of the Department of Fair Employment and Housing, said that he couldn’t remember any instances. However, as was found in Maryland and Vermont, complaints that were filed tended to be lumped in with other violations.

- In Hawaii, Bill Hoshijo, the Executive Director of the Hawaii Civil Rights Commission, tells Demos that “a query of our database found no complaints raising a claim of employment discrimination based on credit history or credit report from enactment in 2009 through the present.”

Hawaii, Illinois, Nevada, Oregon and Vermont allow employees or jobseekers harmed by violations of the law to bring a private lawsuit against the violator. A search of Westlaw and Lexis Nexis returned no cases of individuals pursuing suits in these states.

Greater Public Awareness Would Increase Effectiveness

Since states depend on public complaints to initiate an investigation and enforcement of their employment credit check laws, public awareness of the laws among employees and job seekers is critical to preventing the legislation from becoming a dead letter. It is equally essential that employers are aware of the law and understand their responsibilities so that they can comply. Demos asked state agencies responsible for enforcing the laws about any public awareness or outreach efforts surrounding the laws. No state pursued an advertising campaign (although see page 16 for details about the New York City law, which included a model outreach campaign). Yet some states pursued more outreach than others. It is notable that Colorado, which reported the greatest number of complaints under the employment credit checks law, was also among the states that reported a more vigorous public outreach effort to help workers and employers understand rights and responsibilities under the law.

- The Communications Director for the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries, reports that local newspapers had “initial coverage during the debate, a wave of coverage after its passage, and another round after the law took effect.” He cited four articles to this extent.36

- The Program Administrator of the Maryland Worker Classification Protection Unit tells Demos that in his state, “When a new law goes into effect, we don’t generally do outreach, but we try to post as much helpful information on our website as possible.”

- Elizabeth Funk the Labor Standards Administrator for the Colorado Division of Labor tell Demos that, “ We have a webpage on our Division of Labor website dedicated to this topic… On our webpage, we have a fact sheet available for individuals to download. We also have frequently asked questions on this law. There is also a specific complaint form with accompanying instructions that explains the basics of the law.” She notes that in addition, “In an effort to get the word out, the agency’s monthly and quarterly employer newsletter had articles and blurbs about this new law.” Funk further notes efforts to inform employers of the law. “Since the law passed, the Division has presented to several law firms, employers, and bar associations. During those presentations, we have explained this new law and the available resources the Division has on our website.”

- Bill Hoshijo, the Executive Director of the Hawaii Civil Rights Commission tells Demos that, “There was initial outreach and education on the new law after Act 1 was enacted in 2009.” He included in his correspondence a copy of the press release, as well as a flier that was used for public outreach regarding recent developments. He notes that, “In 2010, we continued to include information on the credit history and credit report protection, including inserts on the new law in all outreach efforts.”

No other states could point to specific media outreach.

A look at other types of employment legislation underscores the importance of broad public awareness. For example, a study of New York City workers finds that employers frequently shirk common labor protections like the minimum wage.37 One study of workers in Chicago, New York City and Los Angeles stunningly finds that 76 percent of workers “were not paid the legally required overtime rate.”38 A study of Philadelphia’s Restaurant Industry finds that 61.5 percent of workers surveyed “did not know the correct legal minimum wage.”39 Regarding illegal pay secrecy policies, Craig Becker, general counsel for the AFL-CIO tells The Atlantic that, “The problem isn’t so much that the remedies are inadequate, but that so few workers know their rights.”40

Ending Credit Discrimination in New York City

New York City’s Stop Credit Discrimination in Employment Act was signed into law by Mayor Bill de Blasio on May 6, 2015 and went into effect on September 3, 2015. The legislation, sponsored by City Council-member Brad Lander, amends the City’s Human Rights Law to make it an unlawful discriminatory practice for an employer to use an individual’s consumer credit history in making employment decisions. While New York’s law is too new to be evaluated for its effectiveness, the narrowness of the bill’s exemptions, the robust public awareness campaign, and strong enforcement mechanisms make it the strongest restriction on employment credit checks enacted anywhere in the U.S. at the time of this report’s publication. However, exemptions that were added to the law as the result of political negotiations should not be considered a model for other jurisdictions.

- How the law was enacted: The Stop Credit Discrimination in Employment Act was the result of a multi-year campaign by a broad coalition of labor, community, student, legal services, civil rights, and consumer groups. The coalition organized New Yorkers impacted by employment credit checks to tell their stories, met with City Council Members and other municipal officials, held rallies and press conferences, published op-eds, and distributed out fliers. Initially, the legislation contained a single exemption, permitting employment credit checks only in cases where the credit check was required by state or federal law in order to avoid pre-emption challenges. However, opposition from the city’s business lobby, law enforcement officials, and other interests resulted in a number of exemptions that ultimately weakened the law. Still New York City managed to avoid many of the broadest exemptions contained in the other state credit check laws discussed in this report.

- What’s in the law: The Stop Credit Discrimination in Employment Act prohibits employers from requesting a credit check or inquiring about an employee or job seekers’ credit history when making employment decisions for most positions. The law contains exemptions for police officers and peace officers; executive-level jobs with control over finances, computer security, or trade secrets; jobs subject to investigation by the city’s Department of Investigation; and positions where bonding or security clearance is required by law. These exemptions were the result of local political compromises and should not be considered a model for future legislation. As part of New York’s Human Rights law, the employees and job seekers are protected from retaliation for making a charge.

- Strong enforcement mechanisms: If an employer requests a credit check in violation of the NYC law, employees and jobseekers have one year to file a complaint with the city’s Commission on Human Rights. Employers found to have violated the law may be required to pay damages to the employees affected and may be subject to civil penalties of up to $125,000. A willful violation may be subject to a civil penalty of up to $250,000.

- A broad public awareness campaign: One distinguishing feature of New York’s law is the public awareness campaign undertaken by the city, which included ads on subways and buses and on the cover of the city’s free newspapers alerting employees and employers about the new law; fliers about the law distributed at subway stations during the morning commute; and a social media campaign with a unique hashtag #CreditCheckLawNYC. The NYC Commission on Human Rights also set up web pages clearly explaining the law and its parameters, offered a series of free “know your rights” trainings for employees/job seekers and “know your obligations” trainings for employers, and published brochures about the law in the city’s ten most spoken languages.

Policy Recommendations

Employment credit checks are a discriminatory barrier to employment. Our research suggests that states motivated to curtail this practice can enact more effective legislation by:

- Avoiding unjustified exemptions: The exemptions in existing state laws are not substantiated by research or other evidence showing that credit checks are valid for the exempted positions. Indeed, no peer-reviewed studies find that a job applicant’s personal credit report is a reliable indicator of the applicant’s future performance on the job or likelihood of committing fraud or any other form of misconduct or crime. It makes sense for credit check laws to include an exemption that prevents state or local laws from conflicting with federal law and potentially triggering a preemption challenge, but no other exemption is empirically justified.

- Launching a public outreach effort: To ensure that workers know their rights and employers know the law, states should engage in extensive public outreach. Currently, media outreach primarily consists of a state website explaining the law. Even the stronger efforts rely heavily on media coverage, which may not occur. Given the relative obscurity of credit check laws, vigorous efforts are required. The outreach effort undertaken by New York City’s Commission on Human Rights should be considered a model.

- Investigating compliance: Labor departments and other agencies tasked with enforcing the law should have the ability to audit compliance, rather than only respond reactively to complaints. The right to pursue individual lawsuits, though it has been under-utilized to date, should remain a part of these laws.

- Clear record keeping: In one state that Demos contacted, California, there was not a central database of complaints that could be used to determine how many complaints had been received. In another, Washington, data are only made available to the public via a complaint form that requires an individual to select a specific business. To better track the effects of legislation, states should maintain a database of complaints and enforcement actions.

Conclusion

The use of employment credit checks creates barriers to opportunity and upward mobility, exacerbates racial discrimination, and can lead to invasions of privacy. Yet because of unjustified exemptions in the laws, lack of public awareness, and a dearth of proactive enforcement, laws against credit checks have not been as effective as they should be. Nevertheless, despite inconsistent coverage and enforcement, laws may have deterred credit checks. The number of employers reporting that they used credit checks when hiring for some or all positions fell from 60 percent in 2010 to 47 percent in 2012, according to the Society for Human Resources Management.41 Both the laws, and the lack of evidence that credit checks are effective have been cited as reasons for the decline.42 Research suggests the laws reduced the use of credit checks by between 7 and 11%.43 However, it is worrying that nearly a decade since the first law was passed, Demos has failed to find evidence that a single employer fined for using an illegal credit check on a prospective employee.

- 1State laws include: Wash. Rev. Code § 19.182.020 ; Ore. Rev. Stat. § 659A.320; 820 Ill. Comp. Stat. §§ 70/1 to 70/30; Cal. Labor Code § 1024.5 et seq.; Conn. Pub. Act No. 11-223; Md. Code Ann., Labor & Empl. Law § 3-711; Haw. Rev. Stat. §§ 378-2.7, 378-2(8); and Vermont Act No. 154.

- 2National Conference on State Legislatures, “Use of Credit Information In Employment 2014 Legislation,” May 6, 2015. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/financial-services-and-commerce/use-of-cred.

- 3The use of credit checks has been increasing, from 13% in 1996 to 60% in 2010, though there was a dip in 2012. Lea Krivinskas Shepard, “Toward a Stronger Financial History Antidiscrimination Norm,” Boston College Law Review, 53: 5, (2012). Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2164633&download=yes.

- 415 U.S.C. 1681(b)(3)(B).

- 5Amy Traub, “Discredited,” 2013, Demos. Available at: http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Discredited-Demos.pdf.

- 6Ibid.

- 7Elise Gould, “2014 Continues a 35-Year Trend of Broad-Based Wage Stagnation,” February 2015, Economic Policy Institute, Available at: http://www.epi.org/publication/stagnant-wages-in-2014/.

- 8Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” Available at: http://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e16.htm.

- 9Amy Traub and Catherine Ruetschlin, “The Plastic Safety Net,” May 22, 2012, Demos. Available at: http://www.demos.org/publication/plastic-safety-net.

- 10Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Report to the Congress on Credit Scoring and Its Effects on the Availability and Affordability of Credit,” 2007; Federal Trade Commission, “Credit-BasedInsurance Scores: Impacts on Consumers of Automobile Insurance,” 2007; Robert B. Avery, Paul S. Calem,and Glenn B. Canner, “Credit Report Accuracy and Access to Credit,” Federal Reserve Bulletin, 2004; MattFellowes, “Credit Scores, Reports, and Getting Ahead in America,” Brooking Institution, 2006.

- 11Jacob S. Rugh and Douglas S. Massey, “Racial Segregation and the American Foreclosure Crisis” American Sociological Review, Volume 75 Number 5 October 2010; Andrew Jakabovics and Jef Chapman, “Unequal Opportunity Lenders? Analyzing Racial Disparities in Big Banks’ Higher-Priced Lending,” Center for American Progress, 2009. http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/housing/report/2009/09/15/6704/ unequal-opportunity-lenders/

- 12“Discredited.”

- 13Federal Trade Commission, “In FTC Study, Five Percent of Consumers Had Errors on Their Credit Reports That Could Result in Less Favorable Terms for Loans,” February 11, 2013. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/02/ftc-study-five-pe.

- 14Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Issues Follow-Up Study on Credit Report Accuracy,” January 21, 2015, Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2015/01/ftc-issues-follow.

- 15Amy Traub, “Credit Reports and Employment: Findings from the 2012 National Survey on Credit Card Debt of Low- and Middle-Income Households,” Suffolk University Law Review, Vol. XLVI:983-995. Available at: http://suffolklawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Traub_Lead.pdf.

- 16Daniel J. Solove, “Privacy and Power: Computer Databases and Metaphors for Information Privacy,” Stanford Law Review, Vol. 53:1393-1462. Available at: http://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2077&context=.

- 17New York Times Editorial Board, “The Credit History Underclass,” May 30, 2012, New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/31/opinion/the-credit-history-underclass.

- 18Society for Human Resource Management, “Background Checking: The Implications of Credit Background Checks on Hiring Decisions,” August 24, 2010.

- 19Use of Credit Information In Employment 2014 Legislation, Footnote 2

- 20City of Chicago, “City Council Approves Law Prohibiting Discrimination Based on Credit History,” March 14, 2012. Available at: http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/cchr/supp_info/city_council_a.

- 21Amy Traub, “The Progressive Victory You Haven’t Heard Of: NYC’s Ban on Employment Credit Checks,” July 9, 2015 The American Prospect. Available at: http://prospect.org/article/progressive-victory-you-havent-heard-nycs-ba.

- 22Use of Credit Information In Employment 2014 Legislation, Footnote 2

- 23United States Senate: S.1837-Equal Employment for All Act of 2013. https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th- congress/senate-bill/1837.

- 24Robert Clifford and Daniel Shoag, “’No More Credit Score’ Employer Credit Check Bans and Signal Substitution,” (2015). Available at: http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shoag/files/no_more_credit_score_employ.

- 25Ibid.

- 26Andrew Weaver, “Is Credit Status a Good Signal of Productivity?,” ILR Review (May 2015). Available at: http://ilr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/05/16/0019793915586382.

- 27Robert Hiltonsmith conversation with Daniel Shoag, December 2015.

- 28http://rjolpi.richmond.edu/archive/PhillipsSchein_Formated.pdf

- 29Demos, “Memorandum on New York City Employment Credit Checks,” September 2014. Available at: http://www.demos.org/publication/memorandum-new-york-city-employment-cre.

- 30Tony Driessen, “Wisconsin AB 367 regarding the use of credit histories for employment purposes,” August 2009. Available at: http://www.wisciviljusticecouncil.org/wwcms/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/0. Eric J. Ellman, “Re: Oppose H.B. 4528,” March 2010, https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/2009-2010/CommitteeDocuments/House/.

- 31U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “American Experiences Versus American Expectations,” July 2015. Available at: http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/reports/american_experiences/.

- 32For example, see Robin Pyle, “Bad credit could hurt your chances of becoming a police ofcer,” Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, September 26, 2010. http://lubbockonline.com/local-news/2010-09-26/bad-creditcould-hurt-your.

- 33Laura Koppes Bryan and Jerry K. Palmer, “Do JobApplicant Credit Histories Predict Performance Appraisal Ratings or Termination Decisions?” The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 2012.

- 34http://www.consumerfinance.gov/regulations/loan-originator-compensation-.

- 35Utilizing Credit Reports For Employment Purposes: A Legal Bait and Switch Tactic?, Footnote XX.

- 36Jessica Van Berkel, ”New law prohibits credit history checks by most employers,” June 30, 2010, The Oregonian. Available at: http://www.oregonlive.com/politics/index.ssf/2010/06/new_law_prohibits_c. Daily Kos, “Oregon Bans Credit Checks by Employers,” July 2010, available at: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2010/07/01/880824/-Oregon-Bans-Credit-Chec. Melica Johnson, “Lawmakers: Credit history shouldn’t keep you from a job,” February 4, 2010, KATU, available at: http://www.katu.com/news/local/83524597.html; Michael Porter and Kathryn L. Kammer, “BOLI issues Credit Check ban regulations,” May 13, 2010, Oregon Business Report. Available at: http://oregonbusinessreport.com/2010/05/boli-issues-credit-check-ban-reg.

- 37Annette Bernhardt, Diana Polson and James DeFilippis, “Working Without Laws,” 2015, National Employment Law Project. Available at: http://www.nelp.org/content/uploads/2015/03/WorkingWithoutLawsNYC.pdf.

- 38Annette Bernhardt, Ruth Milkman, Nik Theodore, Douglas Heckathorn, Mirabai Auer, James DeFilippis, Ana Luz González, Victor Narro, Jason Perelshteyn, Diana Polson, Michael Spiller, “Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers,” 2009, National Employment Law Project. Available at: http://www.nelp.org/content/uploads/2015/03/BrokenLawsReport2009.pdf?noc.

- 39Center for Social Justice, “Shortchanged,” Available at: http://www2.law.temple.edu/csj/files/wagetheft-report.pdf.

- 40Jonathan Timm, “When the Boss Says, ‘Don’t Tell Your Coworkers How Much You Get Paid’,” July 15, 2014, The Atlantic. Available at: http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/07/when-the-boss-says-d.

- 41Society for Human Resources Management, ”Background checking–The Use of Credit Background Checks in Hiring Decisions” 2012. http://www.shrm.org/research/surveyfindings/articles/pages/creditbackgro.

- 42Gary Rivlin, “The Long Shadow of Bad Credit in a Job Search,” May 11, 2013, New York Times. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/12/business/employers-pull-applicants-cre.

- 43See, Footnote 24